Radius-guided post-clustering is a simple geometric consolidation step applied after standard k-means has converged. Each k-means cluster is assigned a radius equal to the distance from its centroid to its farthest point, and clusters whose centroids fall within each other’s radii are merged. This post-processing can recover irregular shapes that k-means alone cannot represent, particularly when k is chosen slightly larger than the underlying structure. It can also correct over-segmentation in a range of settings and recover the ground-truth clustering in structured synthetic datasets, thus often mitigating the impact of moderate k overestimation. The approach does not guarantee improvements over k-means in all cases; for example, it can over-merge nearby compact clusters whose radii overlap, even when k-means itself keeps them separate. The same merge rule can reconnect cluster fragments when the data are partitioned into tiles, provided each tile preserves enough local structure. We evaluate the method on synthetic datasets with diverse shapes and separations and compare it to k-means and several shape-aware baselines. The results show that radius-guided merging is useful as a lightweight refinement step in settings with mild over-segmentation, while its limitations become visible in noisy data and in overlapping circular cluster configurations.

K-means clustering remains one of the most widely used unsupervised learning methods due to its simplicity, speed, and intuitive geometric structure. Its core limitations, however, are well known: it requires the number of clusters k to be specified in advance, and it performs poorly when clusters have irregular shapes or are not linearly separable [1–4].

Many enhancements to k-means have been proposed, ranging from improved initialization strategies such as k-means++ [5] to variations in objective functions and distance metrics. Other clustering algorithms such as DBSCAN [6], hierarchical clustering [7], and Gaussian mixture models [8] address limitations related to shape or distributional assumptions, but often at the cost of increased computational complexity or reduced interpretability.

This paper introduces a simple geometric post-processing enhancement to standard k-means. After k-means converges, each cluster is assigned a radius equal to the distance from its centroid to its farthest assigned point. Two clusters are merged when the distance between their centroids is less than or equal to the sum of their radii, meaning their radius-based boundaries would overlap. The intuition is that moderate over-segmentation with k-means often produces fragments whose radii intersect along the underlying data manifold, enabling a simple consolidation rule that recovers meaningful structure.

The method’s assumption is that radius overlap serves as a coarse geometric signal for identifying adjacent fragments of the same cluster. Standard k-means implicitly defines Voronoi cells, but these offer no principled criterion for merging (Figure 1c). The radius construction introduces a circular approximation around each centroid, providing a lightweight rule for merging nearby regions that likely belong to the same underlying group. Figure 1 illustrates this process on a classic two-circle dataset, where radius-guided merging recovers the intended structure from an over-segmented k-means result.

A proof-of-concept implementation of the method is provided as an extension to scikit-learn’s k-means. It operates entirely in post-processing and relies only on cluster centers and point assignments already computed during the k-means procedure, making it easy to integrate into existing pipelines.

This paper makes the following contributions:

- A shape-aware refinement step for k-means that requires no additional hyperparameters and preserves its computational simplicity.

- A demonstration that modest overestimation of k allows the method to consolidate over-segmented clusters through a simple radius-based merge rule.

- An experimental evaluation on synthetic datasets with irregular boundaries and varying degrees of separation, comparing the method to classical k-means and several shape-aware baselines.

- A discussion of limitations, including noise sensitivity, outlier effects, and scenarios where the method is not appropriate.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews related work. Section 3 describes the radius-based post-clustering method, including its geometric motivation and implementation. Section 4 presents an extension to tiled or partitioned domains. Section 5 reports experimental results on FCPS datasets and on a noisy benchmark, including a tiled evaluation. Section 6 discusses limitations and concludes.

Figure 1. Visual explanation of radius-based post-processing. (a) Naive k-means with k = 2 fails to recover the circular structure. (b) With k = 20, clusters over-segment the shape. (c) Voronoi cells offer no guidance for merging. (d) Circles around cluster centers through the farthest point reveal meaningful overlap. (e) The correct clustering is recovered by radius-based merging of the clusters in (b). This shows how the method fixes over-segmentation—useful for real data where clusters aren’t perfect circles (e.g. sensor groups).

Several clustering methods have been proposed to address the limitations of k-means, particularly its limited performance on non-convex clusters and its reliance on a fixed number of clusters k.

The classical k-means algorithm, first introduced by MacQueen [1] and later formalized by Lloyd [9], partitions data into k clusters by alternating between assigning each point to the nearest centroid and updating each centroid to the mean of its assigned points. The objective optimized is the within-cluster sum of squared distances. In this paper, we use the standard formulation and notation, where cj denotes the centroid of cluster j and Cj the set of points assigned to it.

Density-based approaches such as DBSCAN [10] and HDBSCAN [11] are well known for their ability to identify clusters of arbitrary shape and automatically determine the number of clusters. However, these methods depend on density thresholds and reachability parameters that can be difficult to tune, especially in high dimensions or in datasets with widely varying densities. They can also be sensitive to noise and may struggle to separate clusters in sparse regions.

Hierarchical clustering methods [7] construct nested cluster trees and provide flexible granularity, but they are often computationally intensive and lack a principled mechanism for selecting the appropriate cut level. Other approaches, such as Gaussian Mixture Models [8], offer probabilistic interpretations but rely on stronger distributional assumptions and perform poorly on non-elliptical clusters.

Several extensions to k-means—such as k-means++ [5], x-means [12], and KHM [13]—improve initialization or introduce limited adaptability in k, but they retain the core geometric constraints of the original algorithm. More shape-aware alternatives, including spectral and graph-based clustering methods, can model complex boundaries but typically require additional hyperparameters or incur higher computational cost.

Methods for estimating k, such as the elbow method, the silhouette score, or the gap statistic, address a different problem than the one considered here. They aim to determine the number of clusters before running k-means. In contrast, the present method assumes that k is set moderately higher than the underlying structure and then merges overlapping clusters in a post-processing step. While the resulting number of clusters may reveal the underlying structure in many cases, this is a by-product rather than a k-selection mechanism.

The method proposed in this paper stays close to the simplicity and efficiency of standard k-means while adding a geometric post-processing rule that consolidates over-segmented clusters. It requires no density estimation, distance thresholds, or probabilistic assumptions, and it preserves the intuitive structure of k-means while extending its flexibility in handling irregular shapes.

3.1. Standard K-Means (Recap)

The k-means algorithm partitions nnn observations into k clusters by minimizing the within-cluster sum of squares. In its classical formulation [1,9], k-means alternates between two steps:

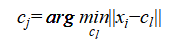

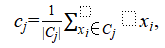

1. Assignment step. Each point  is assigned to the nearest centroid

is assigned to the nearest centroid

where  ranges over all candidate centroids.

ranges over all candidate centroids.

2. Update step. Each centroid  is updated to the mean of its assigned points

is updated to the mean of its assigned points

where  denotes the set of points assigned to centroid

denotes the set of points assigned to centroid  .

.

These two steps repeat until convergence, typically defined by centroid stability or a maximum number of iterations. In the experiments of this paper, we use the default scikit-learn implementation, which runs k-means to convergence.

K-means performs well when clusters are convex and roughly spherical but struggles with irregular shapes and requires the number of clusters k to be specified in advance.

3.2. Radius-based Post-Clustering

To address these limitations, we introduce a simple geometric enhancement. After running standard k-means with an intentionally large k, chosen to be larger than the expected number of clusters, we compute a radius for each cluster  as the maximum distance from its centroid

as the maximum distance from its centroid  to any of its assigned points:

to any of its assigned points:

We then merge pairs of clusters  whose centers are sufficiently close, according to the following merge condition:

whose centers are sufficiently close, according to the following merge condition:

Two clusters are merged when their radius-based boundaries would overlap under a spherical approximation around each centroid. In practice, this rule works well when clusters are reasonably compact and when the over-segmentation produced by k-means aligns with the underlying structure.

The radius definition can be sensitive to isolated outliers: if the farthest assigned point is an outlier, the corresponding radius can become large and lead to unintended merges. Since the method consolidates clusters through merging, the initial value of k must exceed the underlying number of clusters. The exact value is not critical as long as k moderately overestimates the true structure. However, if k is set excessively high—approaching the number of samples—the result is many tiny fragments whose radii are too small to reconnect. This trade-off is intrinsic to the design: the method does not require the exact value of k, only a moderate overestimation.

3.3. Differences from Standard K-Means

Radius-guided post-clustering differs from standard k-means in how it interprets the geometry of the intermediate partition. While k-means assigns points based solely on nearest-centroid Voronoi regions, the post-processing step treats each cluster as a compact region with an extent given by its radius. This spherical approximation allows fragments created by moderate over-segmentation to be reassembled into non-convex or irregular structures, which k-means alone cannot represent.

This difference also explains when the method may diverge from k-means. Standard k-means can successfully separate nearby spherical clusters as long as their centroids lie on opposite sides of a Voronoi boundary. Radius-based merging, however, may combine such clusters if their radii overlap, even when k-means itself keeps them distinct. Conversely, k-means cannot capture non-convex shapes regardless of how k is chosen, whereas radius-guided merging can recover such structures when moderate over-segmentation produces meaningful fragments.

In short, the method modifies how the intermediate partition is interpreted rather than how it is created: k-means produces convex fragments, and the radius-based step unifies them into shapes beyond k-means’ representational capacity.

3.4. Post-Processing Implementation

The merging step is implemented as a post-processing pass after k-means clustering. As discussed in Section 3.2, the method is sensitive to how strongly k over-segments the data. This sensitivity sometimes offers a simple qualitative diagnostic: when coherent clusters are present, the number of merged clusters often remains stable across a range of moderately overestimated values of k. Outside this range, the post-processed result may fragment or collapse. This behavior should not be interpreted as a method for determining the true number of clusters, but it can provide intuition about the scale at which the data exhibit structure.

The merging process itself is implemented as a graph-based procedure. After k-means clustering, each cluster center is assigned a radius, and an adjacency matrix is constructed in which two clusters are considered adjacent if the distance between their centers does not exceed the sum of their radii. Optionally, small or very sparse clusters can be suppressed before merging using a simple points-per-radius heuristic; this filtering is used only in the noisy-data experiment in Section 5.2 and is not part of the core method. The adjacency matrix defines an undirected graph over the set of cluster centers, and all clusters belonging to the same connected component are merged. The resulting labels are then propagated to all points.

This approach avoids iterative pairwise merging and identifies all merged groups in a single pass. It introduces minimal computational overhead and relies only on outputs already produced by standard k-means, namely the cluster centers and point assignments. A proof-of-concept implementation based on scikit-learn is available in the open-source repository [14].

One advantage of the radius-based merging rule is that it allows clustering to be performed locally on subsets of the data and later refined globally. This makes the method applicable to tiled or partitioned domains where clustering must be carried out independently on separate regions.

The geometric intuition is straightforward. A tile boundary is a straight hyperplane, and cutting a cluster along such a boundary produces two convex fragments that retain the local shape and orientation of the original cluster. Because k-means moderately over-segments the data, the centroids of these fragments tend to lie near the boundary, and their radii extend in the direction in which the cluster was cut. As a result, the circles around neighboring fragments typically cross the boundary, allowing the radius-based merge rule to reconnect pieces that belong to the same underlying cluster.

A simple tile-aware workflow proceeds as follows:

1. Divide the feature space into a regular grid of rectangular tiles.

2. Run standard k-means independently on each tile, choosing k as a proportion of the number of points in the tile.

3. Apply the radius-based merging rule locally within each tile.

4. In a global pass, merge cluster centers across tiles using the same radius-based criterion. Spatial filtering can be used to avoid unnecessary pairwise checks.

This approach is useful when datasets are too large to cluster as a whole or when the domain naturally arrives in partitions. The tiled FCPS experiments in Section 5.3 illustrate that the method can reconnect cluster fragments in many cases without modifying the core algorithm. This extension supports tiled or partitioned workflows, although it is not the primary focus of the paper.

To evaluate the proposed method, we tested it on a range of synthetic and structured datasets, in particular the diverse benchmarks from the Fundamental Clustering Problem Suite (FCPS), introduced in [9] and available from [15].

All k-means runs used scikit-learn’s default settings: Lloyd algorithm, k-means++ initialization, a maximum of 300 iterations, and a convergence tolerance of  . Each experiment followed the procedure detailed in Section 5.1, using 100 runs per batch and five independent batches to account for initialization variability. For each dataset we report the interquartile range of the achieved success rates to summarize variability across runs.

. Each experiment followed the procedure detailed in Section 5.1, using 100 runs per batch and five independent batches to account for initialization variability. For each dataset we report the interquartile range of the achieved success rates to summarize variability across runs.

The goal of the evaluation was to assess the algorithm’s ability

- to recover irregular or non-convex cluster shapes in structured synthetic settings,

- to merge over-segmented clusters caused by moderately large initial values of k, and

- to evaluate overlap with labeled ground truth.

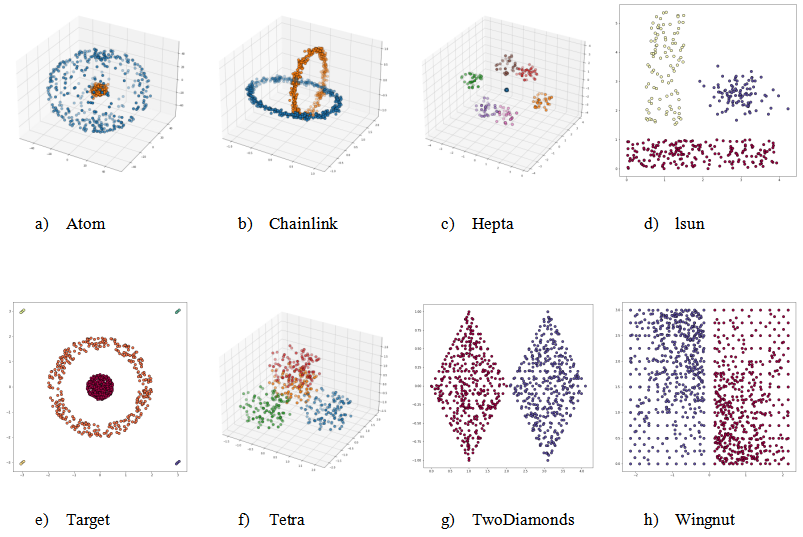

Figure 2 shows the FCPS datasets used in our experiments, each displayed with its ground-truth labels. The diversity of cluster structures—from thin interlocking shapes to dense symmetric blobs—provides a robust testbed for assessing the behavior of the radius-based merging step under a range of geometric conditions.

5.1. FCPS Benchmark Results of Post-Processing Compared to K-Means

The FCPS suite includes a variety of two-dimensional and three-dimensional clustering challenges with ground-truth labels. One dataset, FCPS EngyTime, was excluded because it contains strongly overlapping clusters for which the radius-based merging rule is not well suited.

We first ran standard k-means with k set to the ground-truth number of clusters and evaluated the result against the provided labels. We then repeated each experiment with an intentionally overestimated value of k, applied the radius-based post-processing step, and again evaluated the resulting assignments. Clustering accuracy was measured as the percentage of points assigned to their correct labels.

Each experiment was repeated 100 times with different random seeds. To reduce the influence of unusually poor initialization patterns, this full set of 100 repetitions was itself repeated five times. For reporting, we retained the batch with the highest median accuracy. This procedure was applied identically to both baseline k-means and the radius-based post-processing. All medians and interquartile ranges reported in Tables 1 and 2 refer to the 100 runs of this retained batch.

Tetra was the only dataset for which values of k≠4 did not consistently recover the intended structure. This dataset consists of four nearly touching blobs in three-dimensional space, which is a favorable case for standard k-means with k=4. With this value, post-processing neither improved nor degraded the result. For larger values of k, the inter-cluster distances become comparable to intra-cluster variation, causing many radii to overlap and producing a trivial merged cluster.

Across the remaining datasets, the results indicate that radius-based post-processing either improves clustering performance relative to pure k-means (four out of seven datasets) or reduces the dependence on knowing k exactly in advance, even when k-means already performs well with the correct value of k.

Figure 2. Overview of the FCPS datasets used in this paper, shown with ground-truth labels. These diverse cluster shapes—including rings, overlapping spheres, and complex symmetric forms—serve as a robust benchmark for evaluating radius-guided post-processing. The data sets exemplify Atom—completely overlapping convex hull, Chainlink—linearly nonseparable entanglements, Hepta—nonoverlapping convex hulls with varying intracluster distances, Lsun—varying geometric shapes with noise defined by one group of outliers, Target—overlapping convex hulls combined with noise defined by four groups of outliers, Tetra—narrow distances between the clusters, TwoDiamonds—identification of the weak link in chain-like connected clusters, Wingnut—short intercluster distances combined with vast intracluster distances. Descriptions were taken from [16].

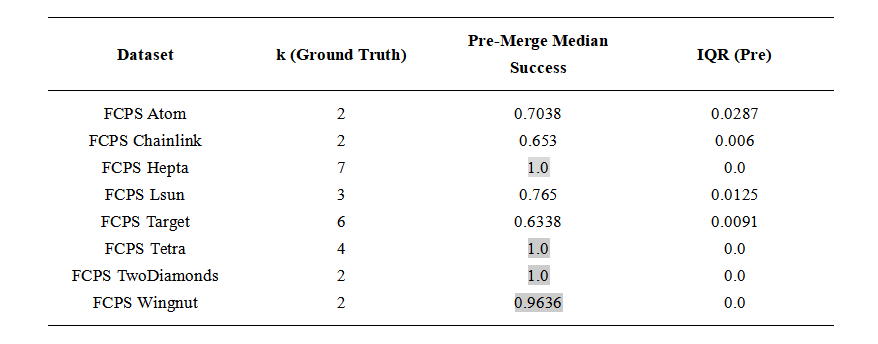

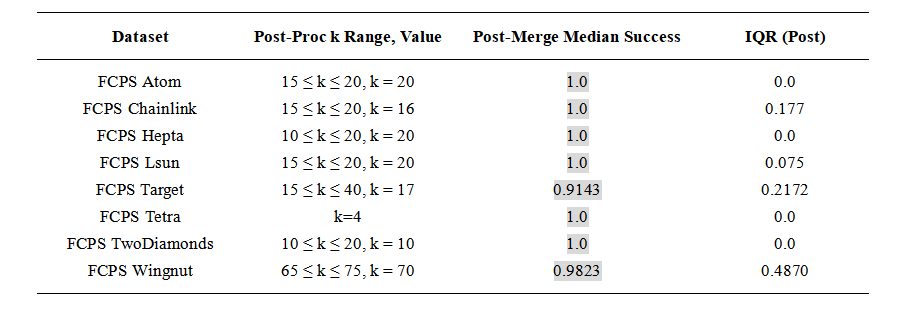

Table 1. Baseline: Clustering performance of standard k-means on the FCPS dataset suite. Median success and interquartile range are based on multiple runs. Cells with a light gray background indicate median success values above 0.8.

Table 2. Clustering performance after radius-based post-processing. The ranges for k give similar results. Cells with a light gray background indicate median success values above 0.8.

5.2. Noise Robustness: Chameleon t5.8k

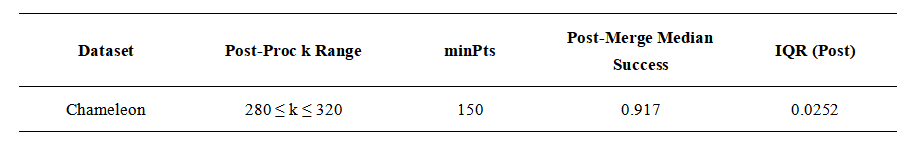

To illustrate the algorithm’s behavior in the presence of noise, we used the Chameleon t5.8k dataset (Figure 3), available from the CLUTO benchmark collection. This dataset consists of noisy background points surrounding several letter-shaped clusters and is included in the supplementary datasets downloadable from the CLUTO website: https://karypis.github.io/glaros/software/cluto/overview.html.

In this experiment we applied a simple post-processing filter that suppresses clusters with fewer than 150 points before applying the radius-based merge rule. This minPts threshold is not part of the core algorithm; it is a dataset-specific heuristic that removes small fragments produced by noise. With this filter in place, the median agreement with the ground-truth labels exceeded 90 percent (Table 3). The approach recovers most of the main structures of the “GEORGE” pattern, as shown in Figure 3.

The choice of minPts is application-dependent and serves here only to demonstrate that small noisy fragments can be suppressed with minimal additional complexity. A systematic study of noise handling lies outside the scope of this work, but this example illustrates that even a simple threshold can improve stability in noisy settings when combined with radius-guided merging.

Table 3. Exemplary clustering performance for a noisy data set.

Figure 3. Chameleon t5.8k dataset.

5.3. FCPS Benchmark Results for Partitioning the Data Space

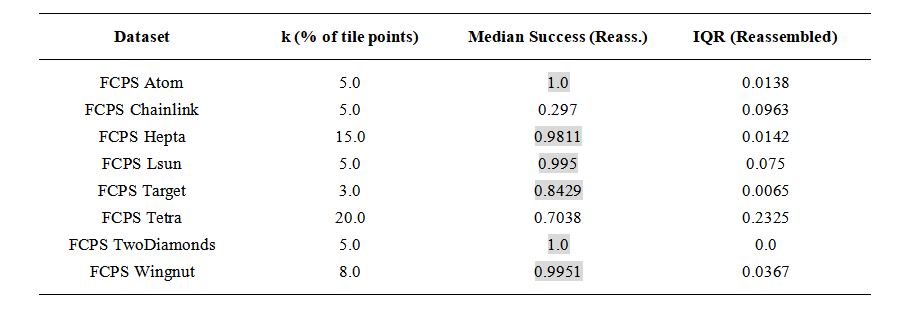

To test the method’s behavior in partitioned domains, we evaluated its ability to recover global structure after dividing the feature space into equal rectangular tiles. This setup simulates scenarios where clustering is performed locally within each tile, followed by a global merge phase based on the radius overlap rule described earlier.

We applied this procedure to all FCPS datasets used in the previous experiments. Each dataset was split into four quadrants by partitioning the feature space in half along the first two dimensions. Local k-means clustering and radius-guided post-processing were performed independently within each tile, with k set as a percentage of the tile’s point count. A final global merge step was then applied across tile boundaries.

The method recovered the intended cluster structures in most datasets (Atom, Hepta, Lsun, TwoDiamonds, Wingnut, and Target; six out of eight), as shown in Table 4. This suggests that the radius-based merge rule can successfully reconnect cluster fragments in many partitioned settings, even when initial clustering is restricted to local subsets of the data.

Table 4. Clustering performance on FCPS datasets after partitioning the feature space into four tiles. Local k is the percentage of data points per tile used for initial clustering. Median success and interquartile range reflect performance after global radius-based merging. Cells with a light gray background indicate median success values above 0.8.

In Chainlink, the two interlocking rings are thin and sparsely sampled. After partitioning, several tiles contained fragments too small or ambiguous to reconnect reliably, and the method typically returned between five and twelve clusters despite the ground truth being two. For Tetra, the behavior reflects the geometric sensitivity observed earlier. The four clusters are nearly touching, and when split across tiles each fragment is small relative to the local structure, making it difficult for k-means to maintain separation. In this situation, post-processing cannot compensate for the loss of global context.

Local choices of k based on tile-level percentages are often workable when combined with post-processing, but there is no universal setting that adapts to all geometries. Domain knowledge or evaluation on labeled subsets is helpful when available. In unlabeled cases, running the method across a range of moderate k values and inspecting stability, as discussed in Section 3.4, can provide qualitative guidance.

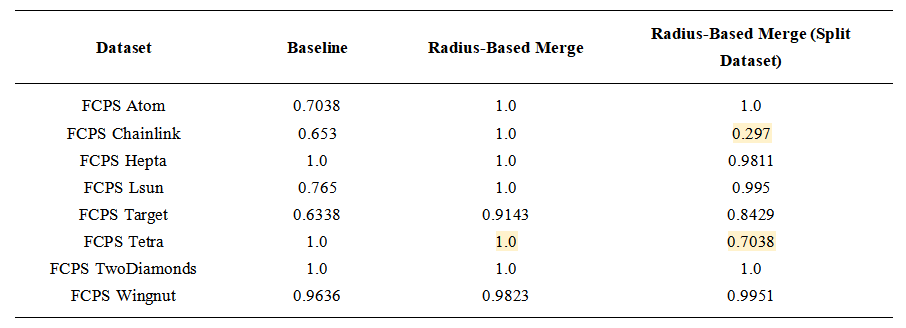

Overall, the results show that the method can recover structure across tile boundaries in many cases, while also revealing clear limitations when cluster fragments become too small or insufficiently informative to reconnect. Table 5 summarizes the core findings across all experiments and highlights both the strengths and failure modes of radius-guided post-processing.

Table 5. Combined summary of the experimental results. Values represent the median clustering success in recovering ground-truth labels: baseline k-means, radius-based post-processing, and radius-based post-processing on partitioned data, assembling the local results to a combined clustering. Results where post-processing or reassembly faced problems are marked in yellow and discussed in the text.

This paper introduced a radius-based post-processing enhancement to the k-means clustering algorithm. By assigning each cluster a radius defined as the distance to its farthest point and merging clusters whose radii overlap, the method can correct certain forms of over-segmentation and recover irregular shapes that standard k-means cannot represent. Because it operates entirely as a post-processing step, it requires no additional hyperparameters, remains compatible with existing implementations, and can be inserted into standard k-means workflows without modification.

Empirically, the method performed well on the FCPS dataset suite, recovering the intended cluster structure in many settings and reducing the impact of moderate overestimation of k. The tiled experiments in Section 5.3 show that the same merge rule can reconnect cluster fragments in some partitioned domains. This extension is not intended as a general scalability solution, but it demonstrates that the geometric merge criterion can function across tile boundaries when local fragments remain sufficiently large within each tile.

6.1. Limitations and Future Work

The method has several limitations. It approximates each cluster by a spherical region, which works well when clusters are reasonably compact but may fail when elongated, curved, or irregularly dense structures lie close to one another. In such cases, radius overlap can either reconnect fragments that should remain separate or fail to reconnect meaningful structure. The method also depends on an over-partitioning step via standard k-means, whose outcome can be sensitive to initialization and unfavorable local minima.

Performance in noisy environments is limited. Outliers can inflate cluster radii and distort merging unless small-radius or low-density fragments are filtered beforehand. Simple heuristics such as minimum cluster size can help in specific datasets, as demonstrated in Section 5.2, but a principled noise-handling strategy remains future work.

Possible extensions include exploring alternative radius definitions (e.g., quantile-based or trimmed radii), adaptive merging heuristics or confidence scores, and formal analysis of behavior under noise. Investigating the method’s performance in higher-dimensional settings and on real-world datasets with heterogeneous densities would also be valuable.

A systematic runtime comparison is left for future work; the present study uses a proof-of-concept Python implementation that is not optimized for performance and therefore not suitable for conclusive timing measurements.

6.2. Conclusion

Radius-guided post-clustering offers a conceptually simple enhancement to k-means. It improves the recovery of irregular shapes, enables post hoc correction of moderate over-segmentation, and reduces reliance on specifying the exact value of k. The method achieves strong performance on several structured synthetic datasets and can reconnect cluster fragments in some partitioned domains. Its geometric intuition, ease of integration, and low computational overhead suggest that it can serve as a practical refinement step in workflows that use k-means as an initial clustering stage.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: All the data and codes used in this study, including the synthetic datasets generated for accuracy evaluation and the Jupyter notebook used for producing the results, are openly available in the project repository at https://github.com/stefankober/radius-guided-kmeans. Benchmark datasets referenced in the text (FCPS and Chameleon) are also available from their respective original repositories as cited.

Acknowledgments: None.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

MacQueen, J. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley, CA, USA, 21 June–18 July 1967; Volume 1, pp. 281–297.

McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Astels, S. hdbscan: Hierarchical Density Based Clustering. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2(11), 205.

Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.-P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996; pp. 226–231.

Jain, A.K. Data clustering: 50 years beyond K-means. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2010, 31(8), 651–666.

Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006.

Hamerly, G.; Elkan, C. Learning the k in k-Means. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–11 December 2003; pp. 281–288.

Schubert, E.; Sander, J.; Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Xu, X. DBSCAN Revisited, Revisited: Why and How You Should (Still) Use DBSCAN. ACM Trans. Database Syst. 2017, 42(3), 1–21.

Gagolewski, M.; et al. Benchmark Suite for Clustering Algorithms – Version 1; 2020.

Lloyd, S. Least squares quantization in PCM. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1982, 28(2), 129–137.

Ultsch, A. Clustering with SOM: U*C. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Self-Organizing Maps, Paris, France, 5–8 September 2005; pp. 75–82.

Pelleg, D.; Moore, A.W. X-Means: Extending K-Means with Efficient Estimation of the Number of Clusters. In Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Conference on Machine Learning, Stanford, CA, USA, 29 June–2 July 2000; pp. 727–734.

Steinley, D. K-means clustering: a half-century synthesis. Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 2006, 59(Pt 1), 1–34.

Kober, S. Radius-Guided Post-Clustering for k-Means. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/stefankober/radius-guided-kmeans (accessed on 22 April 2025).

Müllner, D. Modern hierarchical, agglomerative clustering algorithms. arXiv 2011, arXiv:1109.2378.

Hamerly, G.; Elkan, C. Alternatives to the k-means algorithm that find better clusterings. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, McLean, VA, USA, 4–9 November 2002; pp. 600–607.

Arthur, D.; Vassilvitskii, S. k-means++: The Advantages of Careful Seeding. In Proceedings of the Eighteenth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms, New Orleans, LA, USA, 7–9 January 2007; pp. 1027–1035.