Climate change and biodiversity loss are intertwining at an unprecedented pace, weaving a profound systemic crisis. To address this dual challenge synergistically, this paper proposes a five-dimensional integrated governance framework aimed at achieving a climate-biodiversity win-win. This framework systematically integrates five key dimensions—scientific assessment, spatial optimization, ecological gains, social legitimacy, and development reshaping—forming an action blueprint that spans from scientific foundations to social embedding, ultimately steering toward systemic transformation. We demonstrate that systematically embedding ecological principles into energy and land-use decisions can forge a transformative pathway where energy systems and natural ecosystems achieve synergistic benefits, ultimately steering us toward a future of climate stability, ecological prosperity, and social justice.

Climate change and biodiversity loss are converging at an unprecedented rate into a profound systemic crisis [1]. This crisis originates from a dual set of drivers: firstly, climate disruption caused by greenhouse gas emissions (exceeding 55 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent annually), which has led to global warming of over 1.1 °C [2]; and secondly, direct anthropogenic pressures such as habitat destruction and overexploitation [3,4]. The combined impact of these drivers has severely impacted natural systems: human activities have altered 75% of terrestrial and 66% of marine environments, resulting in a decline of over 80% in the biomass of wild mammals and more than 50% in that of plants [1]. A direct consequence is that the average size of global wildlife populations has plummeted by 73% since 1970 [5]. Even more alarming, populations of freshwater species—a vital lifeline for human water security—have collapsed by 85%, signalling that the crisis is now undermining the very core of human survival and development [5]. Together, this interconnected evidence unequivocally demonstrates that species are confronting an unprecedented threat of extinction in history [3].

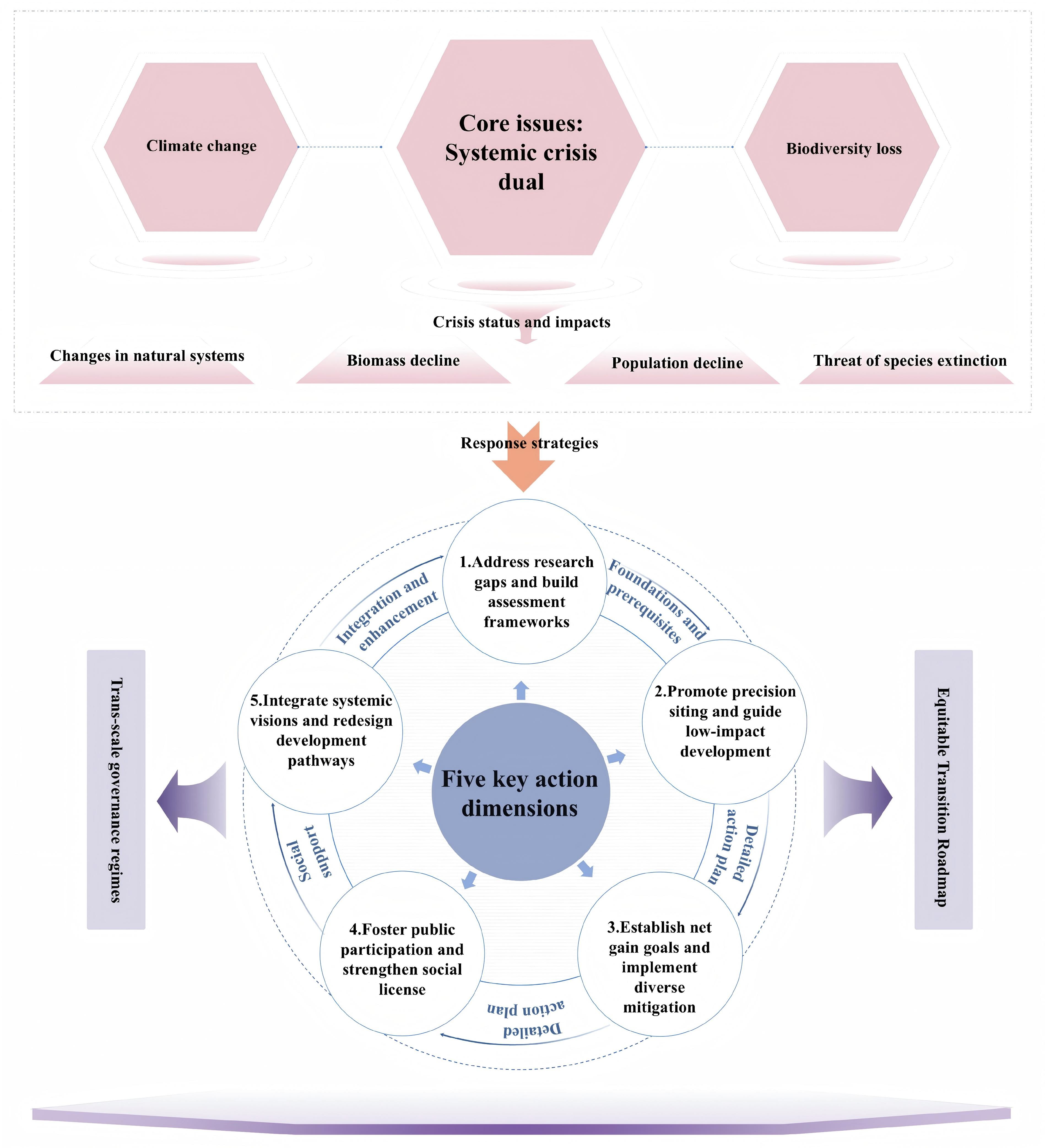

The world is currently confronting a profound systemic crisis driven by the convergence of climate change and biodiversity loss. This crisis originates from the dual drivers of greenhouse gas emissions and direct human pressures, manifesting in severe alterations to natural systems, significant declines in biomass, sharp reductions in wildlife populations, and an unprecedented threat of species extinction. To systematically address this complex challenge, a coordinated approach across five key dimensions is essential: The first dimension, “Addressing research gaps and building assessment frameworks,” serves as the scientific foundation and prerequisite. The second dimension, “Promoting precision siting and guiding low-impact development,” together with the third dimension, “Establishing net gain goals and implementing diverse mitigation,” form the concrete implementation pathways, achieving ecological benefits through spatial optimization and stringent regulation. The fourth dimension, “Fostering public participation and strengthening social license,” provides the social underpinning, transforming public trust into sustained capacity for action. Finally, the fifth dimension, “Integrating systemic visions and redesigning development pathways,” achieves synthesis and elevation by incorporating all actions into a grand vision of systemic transformation. This multidimensional framework embodies a comprehensive governance logic that is science-based, implementation-oriented, socially grounded, and aimed at systemic change (Figure 1).

Address research gaps and build assessment frameworks. The urgency of filling critical research gaps becomes clear when examining emerging fields like deep-sea mining and novel energy storage technologies, where ecological impact assessments remain notably underdeveloped. Equally overlooked are systematic comparisons pitting renewable energy scenarios directly against a “continued fossil fuel reliance” counterfactual [6]. These knowledge gaps highlight a pressing need to prioritize and support targeted research that integrates currently scattered case studies. By weaving together these disparate findings, we can construct the scientific knowledge base necessary for sound macro-level decision-making. Such a consolidated evidence base would naturally pave the way for scientific policy institutions to lead in establishing standardized assessment frameworks, which should then become mandatory requirements for all future project approvals and policy formulation [7].

Figure 1. Conceptual framework diagram.

Promote precision siting and guide low-impact development. Moving from knowledge to action, effective site selection serves as the foremost defense against ecological damage. This begins with the widespread adoption of collaborative spatial planning and ecological sensitivity mapping to accurately identify and prioritize brownfields, degraded lands, and other areas presenting low biodiversity risks [8]. However, identifying suitable locations is only part of the challenge; the core obstacle lies in addressing developers' cost concerns. To overcome this, it is essential to transform “low-ecological-impact siting” from a perceived constraint into a core competitive advantage [2]. This shift can be achieved by deploying innovative policy incentives and tailored market mechanisms that make ecologically responsible development the most economically viable choice [7].

Establish net gain goals and implement diverse mitigation. Building upon strategic site selection, project regulations must actively promote solutions that exceed baseline environmental standards, with biodiversity net gain established as a central objective. This can be realized through three complementary approaches: Ecological Restoration [9], through active habitat rehabilitation within project boundaries—such as planting native vegetation at solar power facilities or utilizing offshore wind turbine foundations to create artificial reef structures; Ecological Compensation [10], by delivering quantifiable ecological benefits in alternative locations to address any unavoidable residual impacts; Circular Design, which integrates circular economy principles across the entire project lifecycle to systematically reduce resource consumption and waste generation [7]. Together, these integrated practices not only produce tangible ecological outcomes but also help mitigate community resistance and reduce long-term regulatory risks. A compelling example is the United Kingdom’s mandatory “Biodiversity Net Gain of 10%” requirement, which demonstrates how binding ecological standards can successfully align development with measurable conservation gains [7].

Foster public participation and strengthen social license. Building on the regulatory foundation for biodiversity enhancement, securing public support emerges as the next critical link in sustainable development [11]. The degree of community acceptance depends directly on thoughtful project design, inclusive ownership models, and equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms [12]. Studies consistently show that communities demonstrate stronger support for projects that not only minimize impacts on local wildlife but also deliver tangible local benefits [13]. To translate this insight into practice, the implementation of participatory decision-making processes—exemplified by initiatives like California's collaborative solar planning program—enables stakeholders to jointly map out “priority development zones” and “no-go areas.” This collaborative approach effectively transforms initial social trust into enduring social license, creating a stable foundation for project success [14].

Integrate systemic visions and redesign development pathways. Ultimately, these individual actions must unite within a transformative systemic vision—one that synergizes climate co-benefits with large-scale ecological protection [15]. This means simultaneously driving emissions reduction and climate adaptation while conserving 30–50% of the planet’s land and sea to form continuous ecological gradients, stretching from strictly protected core areas through sustainably managed landscapes [7]. Achieving this vision demands a foundational rethinking of development itself, grounded in social equity, circular resource flows, and shared responsibility [16]. Crucially, this transition must guarantee that all communities—especially Indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups—receive a fair share of natural capital gains and attain a high quality of life [17,18].

Future research should prioritize quantifying the co-benefits of nature-positive energy pathways, developing cross-scale governance mechanisms, and establishing equitable frameworks for sharing transition costs and benefits across the Global South. This transformation requires a deliberately designed pathway that generates mutual benefits for both energy systems and natural ecosystems. By systematically integrating ecological principles into all energy decision-making processes, we can successfully navigate this comprehensive systemic transformation toward an integrated future of climate stability, ecological prosperity, and social justice.

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Rumschlag, S.L., Gallagher, B., Hill, R., et al. Diverging fish biodiversity trends in cold and warm rivers and streams. Nature 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09556-0

Pörtner, H.-O., et al. Overcoming the coupled climate and biodiversity crises and their societal impacts. Science 2023, 380, eabl4881. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abl4881

Duarte, C.M., Blythe, J., Devlin, M.J. et al. Layering solutions to conserve tropical coral reefs in crisis. Nat. Rev. Biodivers 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00106-0

Wernberg, T., Thomsen, M.S., Burrows, M.T. et al. Marine heatwaves as hot spots of climate change and impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Nat. Rev. Biodivers 2025, 1, 461–479. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00058-5

World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Living Planet Report 2024, WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2024.

Clarke, L., Wei, Y., De La Vega Navarro, A., Garg, A., Hahnmann, A. in Climate Change 2022 - Mitigation of Climate Change (ed. IPCC) 613–746, Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023.

McElwee, P., Smith, P., Ballal, V. et al. The trade-offs between needed renewable energy transitions and biodiversity can be overcome. Nat. Rev. Biodivers. 2025, 1, 561–562. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-025-00079-0

Pascale, A. C., et al. Negotiating risks to natural capital in net-zero transitions. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 619–628.

Ngeve, M.N. Genetic diversity must be explicitly recognized in ecological restoration. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2025, 15, 908–909. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02405-y

Naef, A., Friggens, N.L., Njeukam, P. Carbon offsetting of fossil fuel emissions through afforestation is limited by financial viability and spatial requirements. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 459. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02394-y

Barnes, A.E., Davies, J.G., Martay, B. et al. Rare and declining bird species benefit most from designating protected areas for conservation in the UK. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 7, 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-022-01927-4

Border, J.A., Pearce-Higgins, J.W., Hewson, C.M. et al. Expanding protected area coverage for migratory birds could improve long-term population trends. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1813. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-57019-x

Kelly, L.A., Burns, F., Mordue, S. et al. Recent evidence on the effectiveness of European protected areas for species conservation in the face of climate change. Biodivers Conserv. 2025, 34, 3687–3714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-025-03132-8

Dashiell, S., Buckley, M., Mulvaney, D. Green Light Study: Economic and Conservation Benefits of Low-Impact Solar Siting in California, The Nature Conservancy: Arlington, VA, USA, 2019.

Nowakowski, A.J., Canty, S.W.J., Bennett, N.J., et al. Co-benefits of marine protected areas for nature and people. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1210–1218. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01150-4

Chang, C.H., Erbaugh, J.T., Fajardo, P., et al. Global evidence of human well-being and biodiversity impacts of natural climate solutions. Nat. Sustain. 2025, 8, 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01454-z

Vardon, M.J., Keith, H., Burnett, P., et al. From natural capital accounting to natural capital banking. Nat. Sustain. 2021, 4, 832–834. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00747-x

Bastien-Olvera, B.A., Conte, M.N., Dong, X., et al. Unequal climate impacts on global values of natural capital. Nature 2024, 625, 722–727. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06769-z